In 2021, artists Karen Goulet (Ojibwe) and Monique Verdin (Houma) traveled together around the Mississippi River Delta, planting in the earth braids of cotton torn from old bed sheets and other repurposed fabric scraps. When Goulet returned to the northern headwaters, she planted more pieces around Minnesota. A year later, the strips, which were mostly from used fabric sourced from friends or rummage sales, were collected and woven on a loom, literally and metaphorically merging time and earth into an expression of the river’s heritage and memory.

The Big River Continuum

Conceived as a collaborative exhibition, Aabijijiwan / Ukeyat yanalleh, It Flows Continuously at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum in Winona is the latest in a series stemming from the artists’ participation in the The Big River Continuum project. The program is organized through the University of Minnesota’s College of Biological Sciences with an aim to connect artists and scientists in an exchange that links both ends of the Mississippi River.

The Misi-ziibi—“Big River” in Ojibwe—serves as a literal and metaphorical conduit from its northernmost beginnings near Lake Itasca, Minnesota, to the southern Delta, where it moves through the bayous and into the Gulf of Mexico. The title of the show, translated from Ojibwe and Houma, draws on the perpetual coursing of the third largest watershed in the world and the ways it has connected natural ecosystems, industries, and communities from an origin known in Chata as Misha sipokni, “Older than time.”

Lost Treasure Maps

Monique Verdin has been documenting her Houma Nation relatives living in the coastal bayous of southern Louisiana for more than two decades. In this part of the country, land is disappearing at one of the fastest rates on the planet, with an average of a football field-sized area disappearing every 90 minutes. The loss is attributed to myriad factors, including the dredging of more than 10,000 miles of canals, natural resource extraction, petrochemical pipines, sea level rise due the climate crisis, and more.

The artist’s digital collages, part of an ongoing series titled Lost Treasure Maps, render intimate portraits of her family, especially important Houma women in her life, alongside U.S. Geological Survey maps and other historical imagery.

“Armantine MarieBilliot Verdin, my grandmother, and great-aunt Jeanne were the women who took me down Bayou Pointe aux Chênes to tell me stories about their lives, and how different the territory was before the oil and gas men came in to steal our land and water rights,” Verdin says in a statement, “forever changing our Houma homelands and ways of life.”

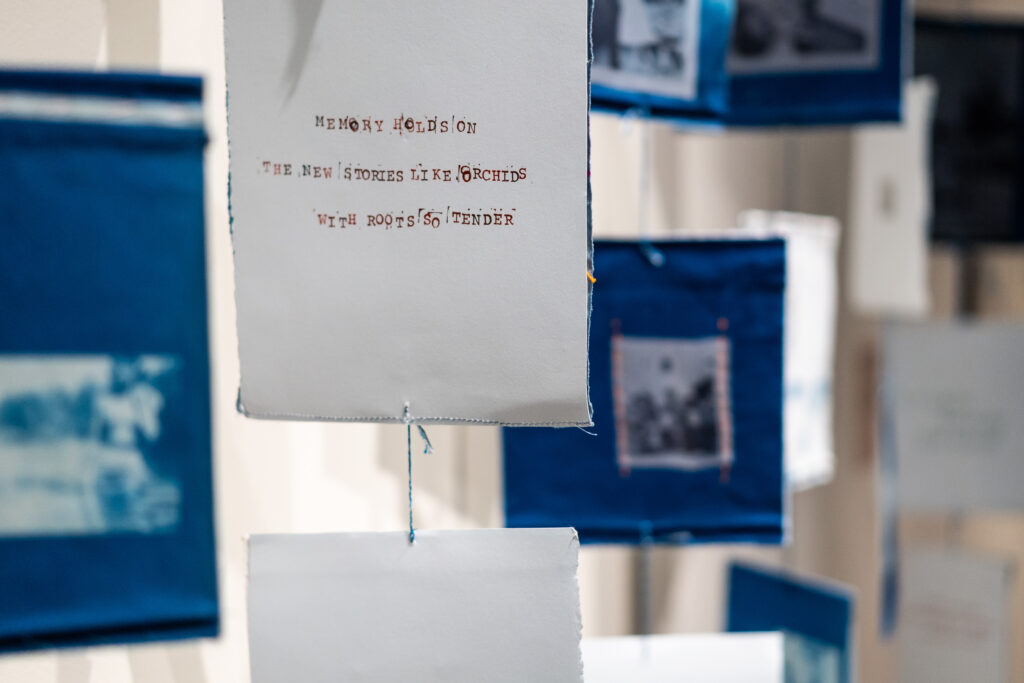

Weaving Misi-Ziibi Memories

In the north, Karen Goulet works with a variety of textile art, including quilt making, surface design, weaving, mixed media, and knitting. When she was growing up, she observed her mother’s avid sewing and her grandmother’s skill as a seamstress, and her father taught her how to do embroidery.

“I am from people who care deeply about the water, the land,” Goulet says. “We are activists, artists, scientists, gardeners, and teachers. I watched my parents and grandparents be very resourceful, frugal, and mindful of their relationships to the earth and each other. You don’t waste things. But you also appreciate the beauty around you.”

The cotton weavings of Misi-Ziibi DNA Memories were made collaboratively with Verdin is a coming together of Goulet’s practice and relationships. “I love, quarrel, and remember with the ancestors each time I hand-stitch. It is a personal ceremony of sorts,” she says.